Four mouse ears bob up and down in the row of seats in front of me. Squealing laughter. Excitement only marginally hushed by their scolding parents. The early morning hour means nothing to them—they’re on their way to meet Mickey Mouse and nothing can ruin this day.

I look up from my computer in time to see a towheaded girl failing to adjust her crooked Mickey ears and staring at me.

“Hi.”

“Hello.”

“I’m going to see Mickey Mouse.”

“Really?!” I exclaim like I had no idea this mouse-eared kid on a plane to Orlando may be destined for the Happiest Place on Earth. “Who are you most excited to meet?”

“Elsa,” she says and immediately breaks into a rendition of a worn out recent Disney favorite.

I smile at her and glance back down at the report I have to finish before this plane lands. My boss is dozing next to me, buying me a few stress-free moments.

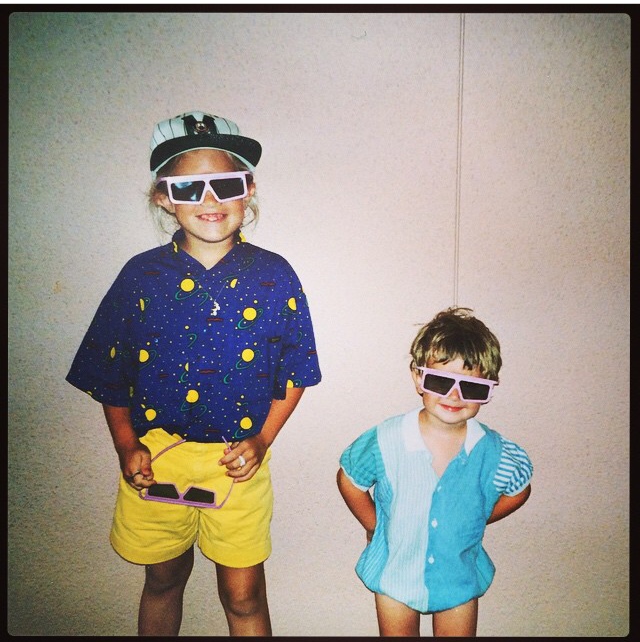

When I look back up, the girl has invited her brother into the conversation and now two sets of crooked ears are telling me about their favorite Disney characters, many of whom I’m no longer young enough (or parental enough) to recognize.

“Are you going to meet Mickey too?” Brother asks.

“Not on this trip,” I tell him with regret.

“Oh,” he says, turning my words over in his head a few times before he looks back up at me, a frown marring his face. “Then why are you here?”

Why indeed.

Four of us are packed in an expensive cab on our way to the hotel where the conference begins bright and early in the morning. It’s late and the highway is dark and in the car, conversation is impact reports and budgets and retention and recruitment and grant applications and I’m trying to remember the last time my parents took me to Disney World.

It was MGM in ’93 and I’m not sure if I remember it or if I’ve just looked at the photos and heard the stories so many times that I think that I remember it.

Up ahead, like a beacon in a heavy storm, a sign illuminated by a million and a half impossibly bright light bulbs stretches across the road welcoming us to Walt Disney World and I have to hold on to the car’s arm rest to keep my body from pressing itself against the window looking for Cinderella’s castle. I have no idea where this desperate childhood moment has come from.

Maybe its the impact reports. Maybe its business cards and appointments and meetings where my under-30 status isn’t appreciated or accredited. Maybe it’s just something in the air here.

At the end of Conference Day One, after I’ve glad-handed and smiled my way through four ballrooms and six general sessions, I’m camped out on the balcony of my expensive hotel room with my overpriced minibar selection looking at the park’s rides all lit up and dotted along the dark horizon. At nine o’ one, the fireworks start and Cinderella’s castle is burning blue then red then purple then gold.

And it is perfect. It is just enough.